Fear and Hunger is messy, spiteful, broken, unpleasant, and unlike anything else. I went through a period of my life where I was unemployed, and naturally, briefly obsessed with it. I’ve played through the first game until I’ve gotten a couple different endings, and I’ve rolled credits on the second game twice now. Developed mostly by Miro and sometimes members of the game’s community, it’s a game with an intoxicating and oppressive atmosphere which even after a couple of playthroughs manages to make me unsettled and tense at my desk. It’s also a game that hates me, and will hate you all the same.

Let me just briefly explain my introduction to this game:

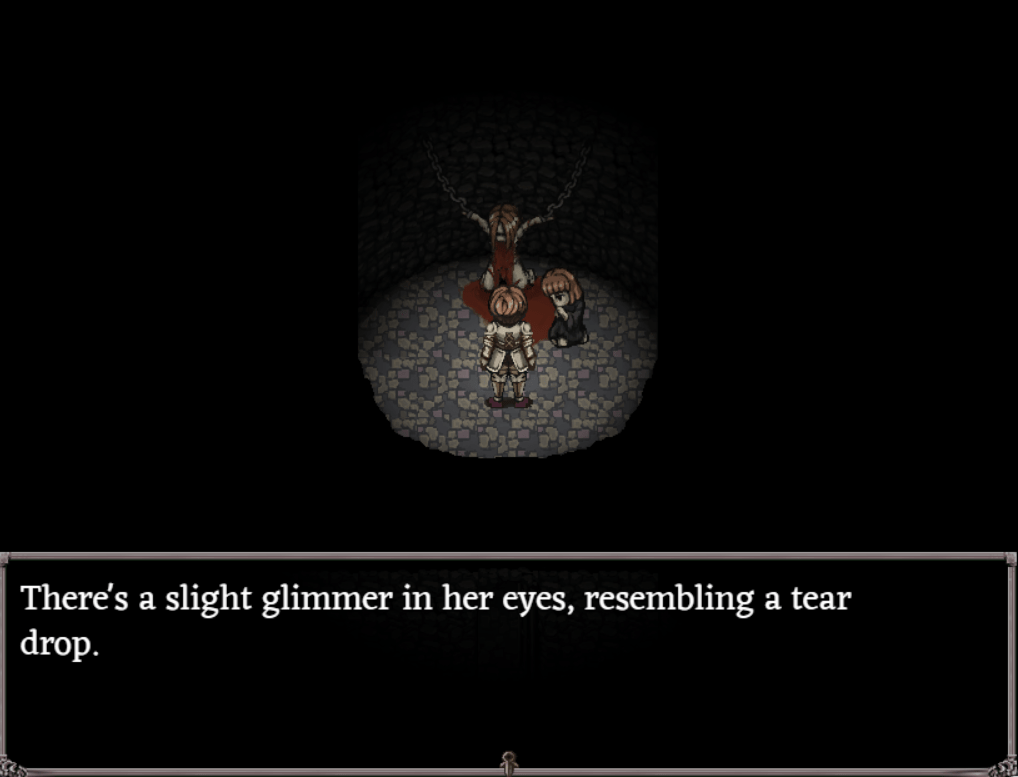

I saw a mutual of mine on twitter a couple of years ago who posted a screenshot from Fear and Hunger, raw, no caption. The post is lost to the inexorable march of time and the death of Twitter, but I’ve replicated the image I saw here.

Fear and Hunger, I soon learned, is a deeply grim dark-fantasy dungeon crawler made in RPG Maker. It’s controversial, cruel to the player, hateful even. I do a very minimal amount of digging while trying to avoid spoiling myself, but the Steam page catches my eye. Both explicit and iconographic depictions of terrible violence, physical, mental, and sexual litter the discussions of this game online. The Steam page features our protagonists cutting their own limbs off with bonesaws, walking in dark rooms knee deep in black bugs, standing in misty fields surrounded by corpses. It markets itself as oppressive and relentless, unforgiving and unique. Some of it makes me roll my eyes just a little, but another part of me makes me lean closer in to my monitor. There is something about this seemingly nihilistic violence that I can’t look away from.

I make my character, reading the character intro for the mercenary and answering the questions. It asks me questions that sound like “at a young age, you had to choose between being a pickpocket or a burglar,” and when I answer, it says things like “you learned steal.” It tells me about my visions of the ancient city of Ma’habre, all the terrible things I see. It tells me I’m hired by the kingdom to find and rescue a man named Legarde inside the prison called the dungeons of Fear and Hunger. These are the kingdom’s own dungeons, and for some reason they have to hire mercenaries to go in there. The character intro says “something is clearly not right about this mission.” That tension hangs in the air, but my mercenary, like me, willingly goes.

Then the game begins and I’m at the gates. There’s a light mist in the air. A dead horse, some crates, and a stone wall with a dark passage in the center. I decide to check out the crates, but pretty immediately, dogs start barking behind me, loud and close. I make the mistake of lingering too long and those dogs come at my mercenary from the bottom of the screen, much faster than I am. (in my character intro, I didn’t learn dash). I wonder if I could possibly walk any slower, and they chase me down before I ever enter the dungeons, snarling and growling ravenously the whole way. We start combat and on one of the first turns the game prompts me to make a coin flip. Like an idiot, I think: tails! I am immediately killed and devoured by a pair of wild dogs.

Then I’m on the main menu and I’m making my character again. I redo it all, quicker this time, but this time I choose differently and learn the skill “dash” in the intro. I head straight for the wide and ominous front gate. I’m greeted with an enemy named the guard, a hulking man with a giant appendage between his legs called the “stinger.” I’m swiftly defeated. Turn one, he cuts my shield arm off; if I survive this encounter, I’ll likely never use a shield in this playthrough again. Turn two, I’ve managed to cut off a leg of his, but it’s not enough. He cuts me down, and the game fades to black, followed by a graphic scene of my mercenary being the victim of this guard’s sexual violence in a dark prison cell. This humiliation, this disempowerment, I realize, is what Fear and Hunger is about.

Here’s how I really feel: I think there’s a lot of places where you could say this game is lame and tasteless and I’d agree. Fear and Hunger has a lot of sexual violence in it, and in my opinion it’s often unsuccessful at anything besides shock value. There are moments where it’s sort of hard to tell if its violent sexual content is intended to be funny or not, and it’s simply not something that works for me. Which is a shame because there are times where the shock and discomfort caused by this stuff is really putting in overtime to sell the tone of the game. There’s a spider-like enemy called the Harvestman that will later be able to kidnap a little girl that can join your party. You’ll be able to find her again, unharmed, except that she’s being pet like a dog by the perverted creature. Losing a fight to this enemy triggers a violent yet delicate scene of sexual violence towards the player that is all the wrong kinds of creepy and scary and humiliating, almost existentially so. It’s deeply uncomfortable and frustrating to experience as a player and I think a more emotionally normal person would just stop playing if it ever happened to them. To be clear, I hate it! But I’m not positive I would change much about it. I guess I wouldn’t generally be in the position where I would create that scene, but still, it makes me wonder where I draw the line, and how artificial these lines are. For some reason, I actually prefer the Harvestman scene to something like what happens with the guards because it’s creepier, stranger, and in this way even more upsetting. But going back and seeing the guard’s exaggerated proportions, I struggle with how childish it all feels! I start to think that Fear and Hunger would be a better experience for me if they just removed a little bit of this persistent sexual violence. But I also think: this is a game about all the most terrible actions of humanity. More importantly, this is the game that Miro made. For better or for worse, this was the vision he had. I can’t change that.

I can make judgments about what it is, though. Fear and Hunger is a game that often fails to deter a pretty vile online presence. I know there’s an official Discord community out there that seems pretty chill, but Fear and Hunger posters are all at great risk of becoming incredibly annoying and volatile. Sorry for being explicit here, but it’s worth mentioning examples of where I think this game is childish and lame: there are certain “situations” which can give you an “anal bleeding” status effect (incurable without dark ritual sex magic). If ever there was an audience who finds “anal bleeding” to be a funny idea, Fear and Hunger has found them. Looking online for examples of these events in the game (because I don’t care to recreate it), you’ll see that YouTube has managed to remove a good deal of it. The only ones that remain are “rape speedruns” posted by people naming themselves after Homestuck characters. Draw your own conclusions: what I’m saying is that no matter what you feel about the contents of Fear and Hunger, there are certainly dark elements of its community, and sometimes the game seems to encourage them. So while I don’t think it necessarily makes the game “problematic” or anything, it does… complicate recommendation. There are of course mods to remove some or all of this if you’re looking to play it without that slimy discomfort, but I just feel wrong using them. The slimy discomfort is sort of part of it, and playing the game I find myself feeling two contradictory things. I shouldn’t have to mod it because it shouldn’t be like this at all! But then, like I said: this was the vision! It’s clearly in the game deliberately, who am I to say what should be? If I’m really feeling that strongly about it, what am I still doing here, stepping on rusty nails and dart traps? And then there’s this third, equally contradictory part of me that somehow finds a lot of appreciation for how openly and unabashedly sicko it is, even when it disgusts me.

After my first couple of deaths, I step away from the game, satisfied that I don’t need to see any more. There is nothing for me here. In a sense, that’s a normal and correct response. Nothing is gained by diving deeper into the dungeons of Fear and Hunger. Still. A few days later, I find myself at my laptop again, outside the main gate of the dungeons, with those horrible and frightening dogs screaming from my speakers. Is it the depravity of the sexual violence that I can’t look away from? The dark allure of what other terrible fates are hiding in the dungeons? That’s certainly a part of it. Just as there is a darkness in the community, in the game, in the dungeons, there is also a darkness in me, a sick and twisted pervert in my heart born deep from probably my own sexual trauma that just can’t look away from this. I won’t ignore that part of me. But still, in many ways it’s also this: from my limited experience, I can already tell that by knowing this place, intimately and deeply, I can master it.

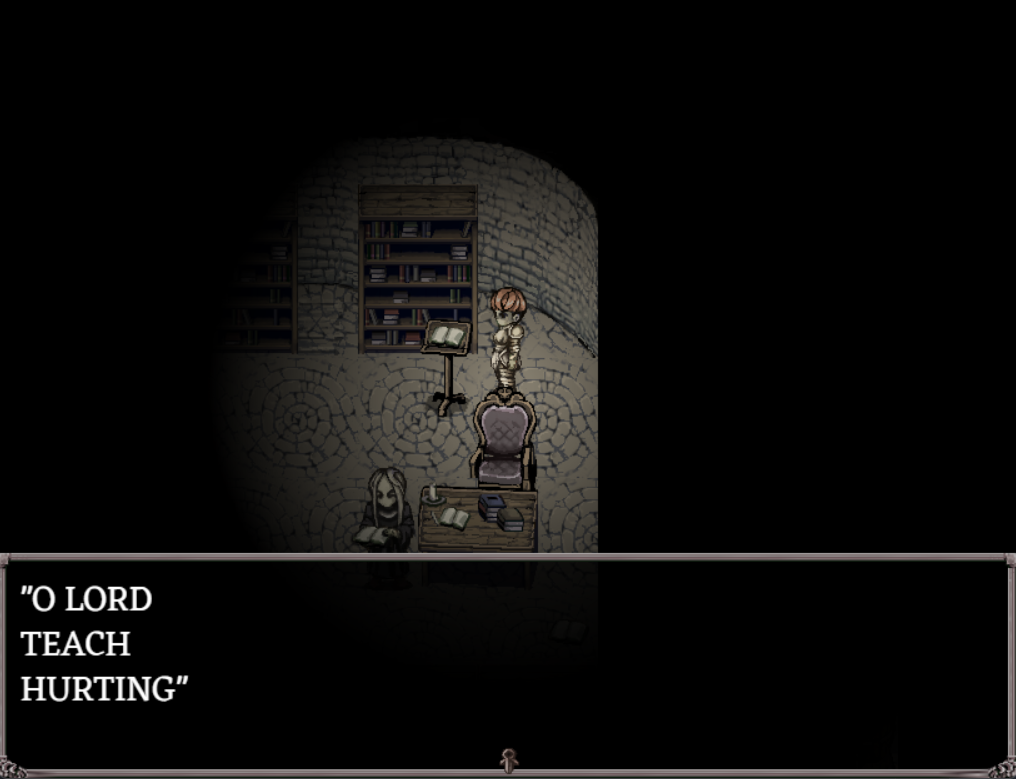

The trick of Fear and Hunger is that it is punishing, unrelenting, dark, and ultimately conquerable. That impenetrable darkness might be the thing that draws some in, but by continuing to stay in these dungeons, I begin to understand it, shining a dim torchlight on every corner and crevice. I learn where I should go back to and where I shouldn’t, what risks to take and what to run from, where and how I can become stronger. I begin to see these things ahead of time too; play more cautiously, with sharper awareness, and I slowly but surely learn how to pre-empt so many of these unfortunate deaths. I am no longer stepping on rusty nails, or letting myself get surprised by guards. I realize that with enough time I can begin to understand how it works on an instinctual level. You have to very quickly learn to be cautious, pay attention, and know the world deeply. Once you can do that, the game opens up to you.

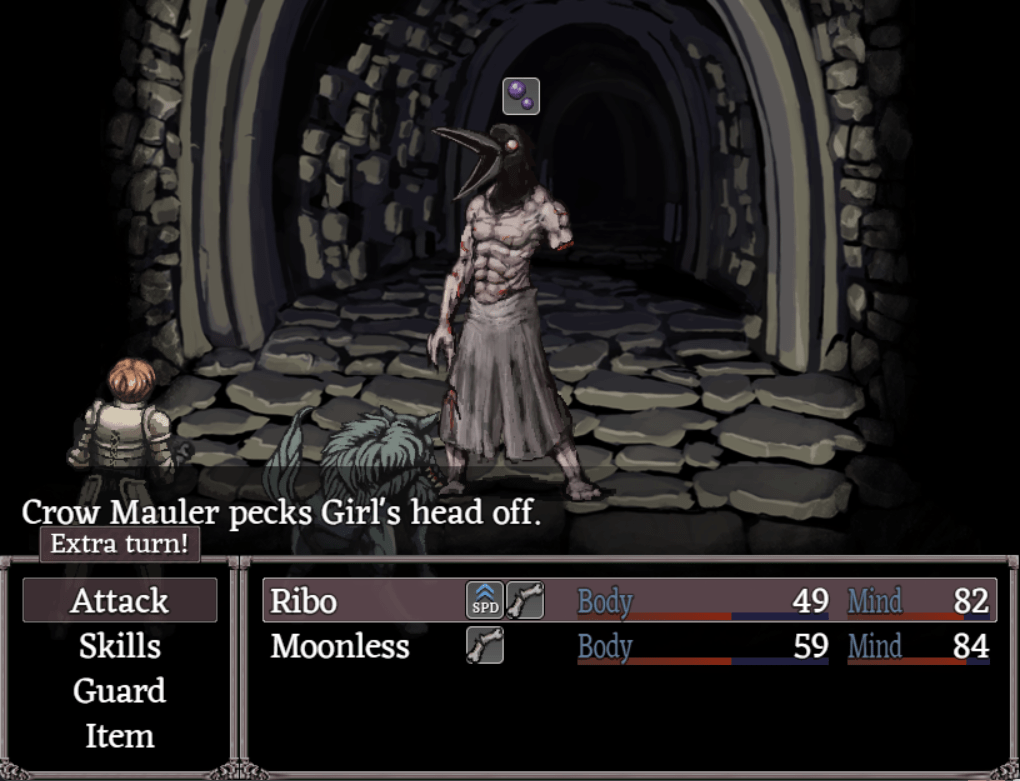

There are lots of ways you can do this, and the first is that you’ll generally want to interact with everything. Crates, barrels, sword stands, armor sets, bookshelves, pots, corpses, and anything else that might vaguely be considered a container. Each one will typically have a randomized item, each item having a chance to be something incredibly useful. You pretty much never want to be finding dirt, but finding an explosive vial can open crucial paths for you or make enemies trivial. What you’ll also learn is that you do not have to fight all the time, and you should often be wary of fighting at all. Most enemies will kill you if you’re unprepared, some will kill you even if you are, and often the best thing to do during an encounter is to run or avoid it entirely. And it all works out this way thanks to the incredibly difficult saving system. You can save by resting at beds placed around the dungeon, but resting at almost any of them prompts a coin flip. Call the coin flip wrong, and instead of pulling up the save menu, you may be interrupted in your sleep by a powerful enemy. Starting an encounter without proper equipment and a plan can be run ending, and the scarcity and danger of save points turns most saves into both a valuable resource and a huge risk. Saving will almost always cost you something. It becomes an even tougher choice when you learn that many of the enemies you can defeat will often take entire limbs from you (incurable without dark ritual sex magic) or give you status conditions that are difficult to heal. Plus, defeating these enemies grants you no experience points, and often very little valuable loot. This is not a game where you will ever level up. There is a progression system, but it mostly revolves around equipment, and later on, skills you can only learn by finding certain items, souls, and being in the good graces of the Old Gods. What this means in practice is that most of the time, you want to avoid encounters with these freaks like the plague. Why fight the guards who will kill and defile you when you can just run the other way and come back with help and better equipment? Why fight the Crow Mauler at all? If it sucks, hit da bricks!

That said, they did make a really neat turn based battle system, so you won’t be able to avoid it entirely. I just mentioned that you can have your limbs permanently removed during combat, but this road goes both ways. Each turn, when you attack or use an ability, you can choose to target either the enemy’s torso or any of their limbs (including the stinger, if you’re fighting the guard). Cut off a guard’s sword arm, and they will no longer be able to hack off your limbs with their giant butcher knife. Sever both of his legs, and the guard loses balance, allowing you to target their squishy and vulnerable head much easier. This is the engine that drives the games combat forward, and certain enemies become little order of operations puzzle boxes for you to solve. With the guards, I tend to have my main character go for the sword arm first, and the rest of my party target the off hand. Then, having protected myself from any limb damage or coin flip attacks, my party targets the stinger while I target the torso for a turn or two until the guard falls. Ghouls require a different strategy: these sunken looking, shambling zombies can and will give you infected wounds, and without the right resources on hand, infected wounds can force you to sever your limbs with a bone saw or else eventually kill you. Otherwise, they’re very weak and it’s often best to just not overthink it and focus the torso from the start to end the fight quickly. You can also use the “talk” skill to tell the ghoul that they are a product of necromancy, which causes the spell to fail and the ghoul to collapse. Every enemy has different strategies needed to defeat them, and almost none of the important encounters are lacking in depth.

The trick to mastering this game, then, is much less about mechanical advancement, and much more about the things you learn from prolonged exposure. This applies to the layouts of the dungeons, the habits of the monsters inside, and the structures of the game itself. Fear and Hunger is a pretty buggy RPG Maker game, and it sometimes feels like it’s threatening to break at any point of weird level geometry or uncommon mechanical interaction. With enough time though, you’ll also learn the very clever and intended ways it instead flexes and bends in your favor.

For example, one of the stronger weapons you can find in the game is a sword called ‘Blue Sin’. it’s a one handed sword with +85 attack, making it incredibly useful and versatile early game, the strongest one handed weapon by far, and the best non-cursed weapon you can get. This is an invaluable find. The only problem is that it’s buried blade deep in a stone wall in the mines, and pulling the sword out causes the mines to collapse on top of you, suffocating you and your entire party under stone and leaving you dead and buried deep under the dungeons. I believe this was intended as a little joke! In the original release of the game, you actually weren’t able to get the weapon legitimately. However, after seeing somebody try a particularly neat method to get the sword, Miro went ahead and added it in officially.

After you draw the sword from the stone, the caves around you begin to rumble and you have a brief moment where you’re able to pause the game. Pausing the game allows you to access the inventory, and if you happened to have found a book called “Passages of Ma’habre,” you have just enough time to open this book. Reading this book teleports you for just a few minutes to Ma’habre, the ancient city of the gods, allowing you to to avoid the cave in, keep the sword, and explore the city for a bit to get some items and see an environment wholly unlike anything you’ve seen in the game so far, right before you’re eventually brought back safely to what is now a devastated tunnel blocked off with piles of stone. There are tons of weird little quirks like this in the game that you can use to become stupidly powerful; all things that are certainly intentional but have a sort of game-breaking quality to them. You can later find certain items or skills which grant you the ability to teleport several tiles at a time, or walk on water, or turn water into wine (which will give you unlimited mind recovery if you use it right). There’s also items called “empty scrolls” that you have a small chance of finding in most bookshelves which, if used properly, can teach you any ability or give you any item in the game. There are only one or two hints to the fact that you can do this in Fear and Hunger; it’s just something you have to figure out yourself or find through the community. All of these little mechanics carry with them huge sequence breaks if you’re that type of player, and what I’ve mentioned here so far is only beginning to scratch the surface on the weird exploits hiding in the dungeons.

There is an alchemist you will meet deep in the dungeons: Nosramus, who has used the knowledge in this place and the power the gods have here to make incredible discoveries and do incredible things. Nosramus is an androgynous, long haired fellow who looks similar to the dark priest we have the option to play as, and he gives you playful hints and foreshadows certain revelations throughout the game whenever you encounter him. It is implied that Nosramus has become enlightened through the dark knowledge hidden here, and has used that enlightenment to gift himself the otherworldly power and everlasting life needed to pursue his academic interests. Deep in the darkness of this place, among all the blood and gore and torture, he has used the secrets of Fear and Hunger to reach immortality. Nosramus is an echo of the player character in this way; somebody who was lead to this dungeon under unfortunate circumstances, but has used his experience with it to gain total control over it, rendering its horrors into his playthings.

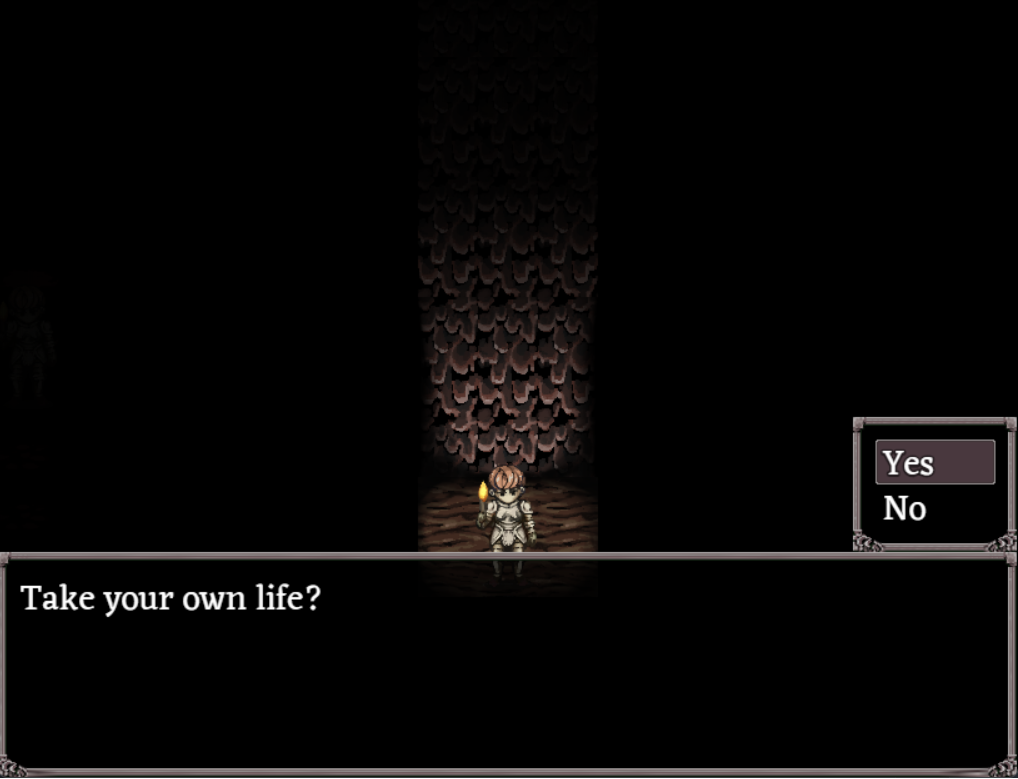

The hurdle of this game is the same thing that draws you in. It is tough on you. It wants to kill you. It barrages you with constant horror, loss, violence, death, sickness and injury, all oftentimes incurable or otherwise permanent (except by dark ritual sex magic). This is why people come to this game, and why people come to these dungeons: knowingly or not, they come here to be hurt, badly. The players of Fear and Hunger want the suffering and the cruelty, and they want it brazenly on display, uncensored and unfiltered even by one’s own creative restraint. That pain, and your ownership and eventual mastery over it, is so intoxicating and satisfying that it demands you delve deeper. Past the dungeons, past the mines, through the impossible ancient city and into the rotting body of an Old God.

Yet Fear and Hunger, despite all the mastery it allows for, is ultimately a fatalistic and cruel game about four unlucky adventurers who are doomed before the game even starts, before any of them even meet one another. They were doomed, all of them, the moment the visions of the ancient city of Ma’habre began to appear in the dark recesses of their minds. The dungeons of Fear and Hunger are a place where people go and are forgotten, go and do not return, go and die, or much worse. If you’re a player who doesn’t want your characters to be defiled, dismembered, killed, and forgotten at the bottom of a toilet in the most evil place on earth, you might not want to delve too deep. I, for some reason I can’t math out, am drawn to this darkness, and will continue to come back to this hateful place.

Leave a comment