In 2015, a little RPG you may have heard of called Undertale was released. At the time (16 year old kerry lmao), my favorite video game that I had ever played was Fallout: New Vegas, and something I had admired about that game was the diversity of scenarios and solutions it had on offer. I remember pretty vividly playing the Ultra Luxe casino quest several times, loading backwards and forwards through my dozens of quicksaves to test out different skill checks, dialogue trees, locations, and routes. Of the video games in my life at the time, pretty much all of them included a decent helping of murder. It was novel to me when there were games where I could avoid violence through other kinds of conflict resolution! At the end of the day, I was a goody two shoes, and I always wanted to do the version of the quest where the least people had to be killed. But here’s the eternal problem we can’t seem to solve: killing people is awesome. I didn’t just want to see the results of the pacifist routes; I was using those quick saves to Kill Everything. What happens if I kill that guy? What happens if I eat this other guy? There was an itch that motivated me to play more and more of this game, and that itch was sometimes a violent one, only ever satisfied by learning everything I could about it. All of these different routes and different endings; the developers made them because they wanted a reactive game that makes every playthrough unique. I wanted to see it all.

Around that time (once again 16 years old), I thought this seemingly unstructured player choice was so impressive, and it changed the whole way I approached games at the time. Little teenage me had begun to ask herself; why haven’t there been more games like this before, where you have more choices for conflict resolution besides violence and battles? Must it always be small guns, melee weapons, explosives? When Undertale released, I was fully bought in. It’s funny and unique and strange and earnest and I loved it. What I didn’t expect, and what I liked most about it, is that Undertale was laser focused on this feeling at its thematic core: it was not only about wanting to find peaceful solutions to conflicts in video games, but what it means for somebody to want to see all the despicable evil shit too. Playing the route where you kill every character in the game (called the genocide route by players) is an extended meditation on this question. You clearly like these characters and enjoy spending time in this world, or else you wouldn’t still be playing the game. What does it mean that you like this world so much that you want to destroy it just to see what happens when you do?

The first two chapters of Deltarune have been available to play for some time now, but with the release of Deltarune chapters 3 and 4 several weeks back, I’ve finally had my moment to play through the whole game so far. And it’s great! I hadn’t played through most of chapter 1 or any of chapter 2 until now, and I like it. I may even like it more than Undertale.

But it’s not really what I’m here to write about.

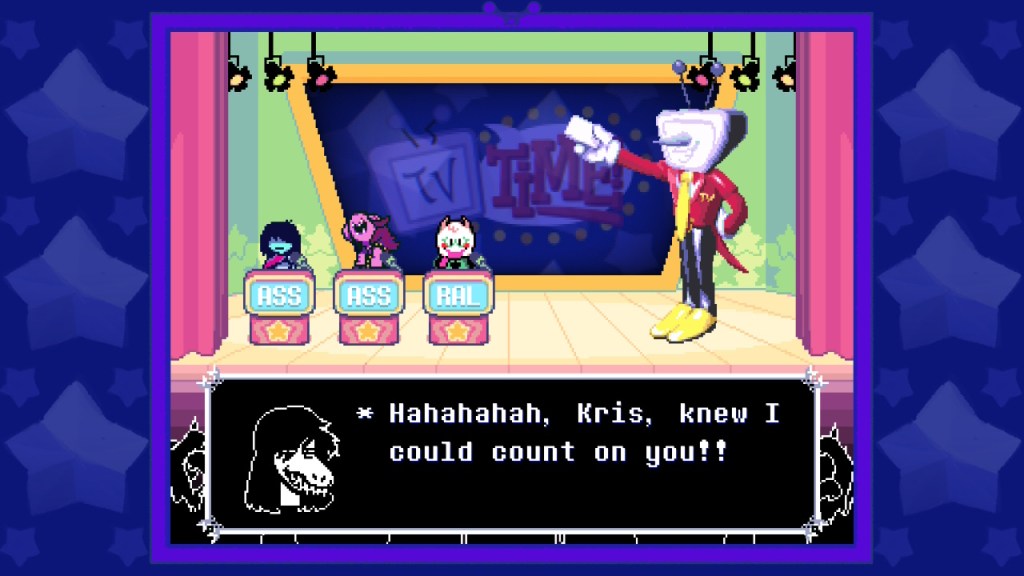

Don’t misunderstand me, I think there’s a lot to say about this game. I love the damaged families of Deltarune, and the fact that they’ve avoided showing a single stable nuclear family in the whole game, and that we don’t see Susie’s home life at all. I really like the escape from reality that the dark world offers to Susie and Kris, and it’s parallel to the escape from reality often found in RPGs like this one. I have lots of feelings about the difference between the “genocide” route in Undertale and what everyone calls the “weird” route here. I really like that the focus here is less on the outright violence of the RPG player, but rather the corrupting influence of the player’s absolute agency we have on the heroes, their friends, their world. I super love the way the battle system in Deltarune has complicated the more simple turn based battles of Undertale just by adding a party with different abilities and a couple resources to manage. I love the flexibility of the battle system, and love every time they change the rules for a single fight or a one-off joke. I’m interested in the instances where you have to “fight” if you want to “win” a battle, and what it means to want to win so badly that I choose to fight when I normally wouldn’t. Deltarune is clearly interested in the persistence of a player and their player character, who continues even though — or perhaps because — they’re meant to lose. Also: I fucking love Susie! Fluffy boys and mean girls… Ralsei with a beard… objects coming alive with the power of love… Deltarune is incredibly thematically rich from start to finish and there’s a lot to like about it.

But mostly, finishing what Deltarune has to offer so far has left me curious and wanting more. I really want to see what’s next with this game, and I just wanted to keep playing when I was done. So I did the natural thing and began to look backwards at what came before it. What were the games like this that inspired Undertale and Deltarune, games with metanarratives about the cruelty of the RPG player and the peaceful alternatives to fighting. What was out there before Undertale, Homestuck, and that one Earthbound romhack Toby Fox made where Dr. Andonuts calls you a slur? So, I pivoted. Sike! We’re talking about something else!

moon: remix RPG adventure (1997)

18 years before Undertale, moon: remix RPG adventure‘s greatest strength was that it was equal parts totally unique and effortless to understand. Developed by LOVE•de•LIC inc. and written by Yoshiro Kimura, moon is a game about a world that has been devastated by a great Hero, who in his travels kills monsters and animals for experience and raids everybody’s houses for loot. While the Hero levels up and becomes stronger through violence, you play as a young boy who, sucked into the game world isekai style, levels up and gains experience through gathering love. Love is the most important and precious thing in the world, and you can find it everywhere just by walking around. You find love by doing all sorts of things: witnessing something interesting, helping a friend, or bringing back the lives of the animals slain by the Hero. Teaching your gramby’s dog a trick, smelling the pollen, lighting a fire in someone’s heart… That is Love. This is Love. moon, a game that markets itself as an “anti-RPG,” is all about collecting love from the people you meet and the places you go.

moon opens with our young protagonist sitting down to play an RPG in front of the GameStation. He plays a game called moon, an extended parody of the JRPGs like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest. There’s a long opening exposition, telling of dragons formed from shadow, a princess in danger, and a prophesied holy hero, but the boy skips through the text before we actually get the chance to read most of it. Tasked by the king to travel the world, grow stronger through experience, and slay the dragon, for the next 10 minutes we follow the Hero as they battle snarling dogs, terrible monsters, and the Penultimizer. The world of this RPG is intentionally generic; it’s all 16 bit graphics with bland, washed out colors and NPCs with no personality or life. moon, the fictional RPG within our game, sucks. But one night when the boy goes to bed, the TV turns back on and he’s pulled into the screen. He falls into the world of the game, and we begin to see that world from a completely different perspective. Embodied outside of the context of the RPG, the world of moon is rich and diverse in visual style. Now, with the game having properly begun, moon is a strange, evocative, and colorful multimedia gallery of characters and settings. Idiosyncratic weirdos now work, sleep, socialize and live as colorful sprites about town, animals are placed throughout the world as clay figures, everybody walks on pre-rendered colorful backgrounds, we find illustrations and photographs everywhere, and the plain and repetitive chiptune heard before is replaced with an atmospheric quiet. The world is only occasionally dotted with music, but the music is a diverse blend of genres and styles, between fun and weird drum and bass beats like Affection for Beauty, piano ballad renditions of Clair de Lune, and lighthearted ambient tracks like Water Scene. I really encourage you to listen to these; they’re just lovely, all for different reasons, all making the world feel large and full of wonder.

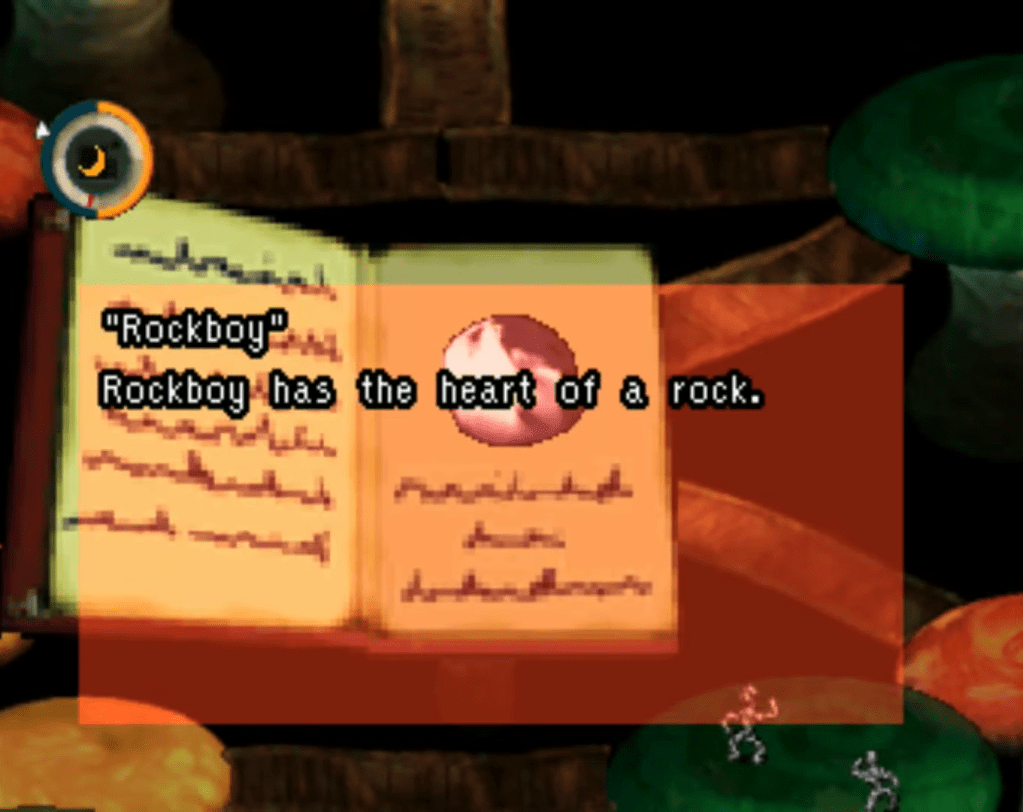

In moon, there is no battling. Just as Ralsei had insisted in Deltarune, this is a world where you never have to fight. Instead, you follow the trail of destruction left behind by the Hero, cleaning up the mess he’s made and rescuing the creatures he’s defeated. You’ll find the clay figure corpses of those the Hero has defeated littered across the world. Their souls now wander, separated from their remains. You reunite them by catching the souls. Sometimes, this is simple: you find the soul in a field, and you just walk up and grab it, causing it to drift back to its body. Other times, this is much more complicated, and involves teaching dogs summon magic, intimidating shyrocks to move, or finding the sad song of a harpflower. You know what they say: you tell a dog to summon and his bark might call a little bird. But teach a dog to summon, and he might call upon the soul of Snacky the snake into the open, allowing you to catch it. I have heard this turn of phrase said many times.

I’ve also heard it said before that love is about paying attention. Investigate the remains of the slain animals, and their description will sometimes tell you about their habits and what they enjoyed doing before they were killed. It’s doing these things that will help to bring them back to life. Talk with the people of this world, and they’ll tell you a little about their lives. Spend time following them around and you’ll get an idea of their schedules. Much like our world, the world of moon exists on a seven day weekly cycle, and much like us, the inhabitants of this world have a schedule. During the day, Bilby and Fred guard the castle in Castle Town. Every Solarsday, Bilby goes to the balcony to run test flights on his model planes for his son. On Crescenday, Tearsday, and Coinsday, Bilby goes to the bar at night. When Bilby goes to the bar, Fred sneaks away to practice his singing in the throne room. Every character in the game works on schedules like this, and the more you follow these characters’ stories, paying close attention to the things they say and the ways they act, the more love you’ll find they have to give.

This is all there really is to the game mechanically speaking, and in this sense moon is incredibly simple. You’ll travel the world, catching the spirits of animals, talking to people, showing them items, eating the cookies Gramby baked, and finding little ways to make them all happy. The skills that moon tests from the player is the same as the ones tested by love: attention and patience. Just walking, and in fact doing most things in this game, is slow. Getting from place to place mostly means waddling quietly around the world, day and night, listening to the ambient sounds of the leaves and the birds. Time is important in moon, and often there are small weekly windows for you to try out ideas and complete tasks. But moon is a game that wants you to take your time with it, too. I walk around slowly in this world, and as I do, it feels like time slows down with me. It’s relaxing, low stakes and low stress. You have to enter a meditative sort of state as you play, listening and following along with the game patiently and quietly. Love makes you wait sometimes. The solution to lots of puzzles in this game is to put down the controller and kick back for a few minutes. It wants you to sit in those quiet moments, to spend that time thinking and feeling.

This is the difference between us and the Hero: love and attention. The Hero doesn’t seek out love, he seeks out experience. He wants to fight, he wants to win, he wants to conquer. He wants stronger equipment, more powerful spells, a higher level. He is the part of us that wants higher numbers to show up when we attack in battle. He sees the world differently than we do, in less detail and with less love. Where he sees a castle town without character, existing only for you to stop in and loot before you continue on your journey, we see a bright town where each person has a story, a secret, and love they carry with them. What appears to the Hero as a home with a single box to loot is to us a local barkeeps night bar, where a sad baker drinks. The Hero would never approach this baker or his home, but when we do, he very strangely reveals himself to be made of bread. Each day he bakes a new head for himself and sells the old one, and each day forgets that he does this. Like, yeah man, sure! There is so much character in this world. The Hero misses the idiosyncrasies and oddities of this worlds creatures because of his one track mind towards power. The Hero is not interested in stopping to smell the flowers, or learning about the lives of the people in this world, or living alongside them as equals. We are.

Of course, we are the Hero, too. At the beginning of the game, you name the player: I named him “ribo ♥,” but he’s often mistaken for a boy who died a few years back, named “RIBO ♠.” This all caps version of myself, thought to have already died, is the Hero. You are the “player” and the Hero is the “PLAYER.” When the boy plays the game in the very beginning, he is carrying out the Hero’s violent path. When we encounter the Hero later, we are encountering ourselves, the things we do in these digital worlds. We are no match for him, and with each encounter, simply being touched by him sends us flying out of his path. We are powerless before the violence of the Hero, of ourselves, but that’s okay. We are the other side of the coin too, the kindness, compassion, curiosity, and love. We walk the same path and do our best to undo that violence. All we can do is listen to the ones in our lives and try to set things right, and just by trying we make friends with people and animals everywhere we go. I hope by now that the thematic similarities to Undertale and Deltarune are clear, but if not, let me say this: Undertale, too, is about this tension within the RPG player. The players capacity for violence and the players capacity for love, and the players need to do both, to do everything, to do it all. Toby once said in a tweet that moon: Remix RPG Adventure was a big inspiration for Undertale. Having now played the game, the influence is obvious. Yoshiro Kimura and his studio Onion Games are now close to releasing Stray Children this year. Playing moon has made me really excited to see what comes of that!

I’d like to speak about the ending a little bit, but I’m wrestling with the fact that I’d rather you just go and play moon. I will say this one detail, which I think is crucial to understanding the game: this dichotomy between the player and the PLAYER eventually becomes the central focus. In the end of the game, it’s revealed that the prophecies told on “rumroms,” technological chips which contain information about the world and its characters, show two possible endings to the story. One is an ending to the player’s story and one is an ending to the PLAYER’s story. The central question of the game then become a question of which story we want to see. Do you want to see the Hero slay the monsters, or do you just want to move on? Do you want to see the story of the video game, the programmed world in which these characters all live and you have escaped to? Or do you want to stop escaping to this clockwork fantasy, take what you’ve learned about love, and go? You are free to open the door and go find more love somewhere else. This is what moon tries to pass on to its players: there is a love in this world so powerful it can’t be quantified or qualified with numbers or levels. More than anything, this is a game that tells you to open the door and find it.

I’ve been trying to listen. Lately, every day on my walk to work, I’ve passed by a large and terrible group of menacing geese. There must be dozens of them, always in the same spot, often walking in the street, stopping traffic, intimidating pedestrians. They’re a real group of bastards. Today, I saw them and felt compelled to just spend a few moments nearby, waiting for nothing in particular, looking at them pick at each other and wander in peace. I felt that peace with them, the peace felt between a flock, all silently mirroring one another. I sat criss-cross applesauce in the grass, watching them as they watched me, each of us curiously admiring the other. Soon, a small group of them turned and waddled in perfect formation across the road. A mother followed by her children. I felt love, then; love born from the attention I had paid to the world and the care I had been trying to give it. That love, in whatever small way it manifests, is worth something. It has to be.

Leave a comment