Probably the only thing I like as much as I like role playing games is skateboarding. I love skateboarding, man. I had skated here and there before, but I started really and truly learning how to skate sometime in 2020 along with seemingly everybody else in the world at the time, and for a few years it was one of the only things I thought about. Skateboarding to me felt like freedom: from shame, from pain, from feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. When I first began skating, I thought of it in a similar way that someone might think of yoga. For me, skating had me thinking of my body in entirely different terms than I usually do. It’s all about dexterity and precision, and just a couple centimeters difference in foot positioning can totally make or break a trick you’re working on. In this way, despite style being so important to skateboarding, improvement is often found not in others perception of you but instead in what feels natural. Finding the most natural way to do a trick that works for you is a meditative process. Skateboarding asks of you to have a very specific attention to and control of your body, and to center yourself in that attention and presence. I would call it an escape, but it’s almost the opposite. It’s something that completely grounds you in your body, and requires of you a mind-body connection that can be difficult under normal circumstances if you’re prone to dissociation or feeling distant from yourself like I am.

What I’m saying is that I know how to do a kickflip. I mention this not to brag — I do not at all have bragging right-level skills when it comes to skating — but instead to make known my familiarity with the topic, as today I seek to answer probably the most important question in the history of skateboarding itself.

Is Tony Hawk’s Underground a role playing game?

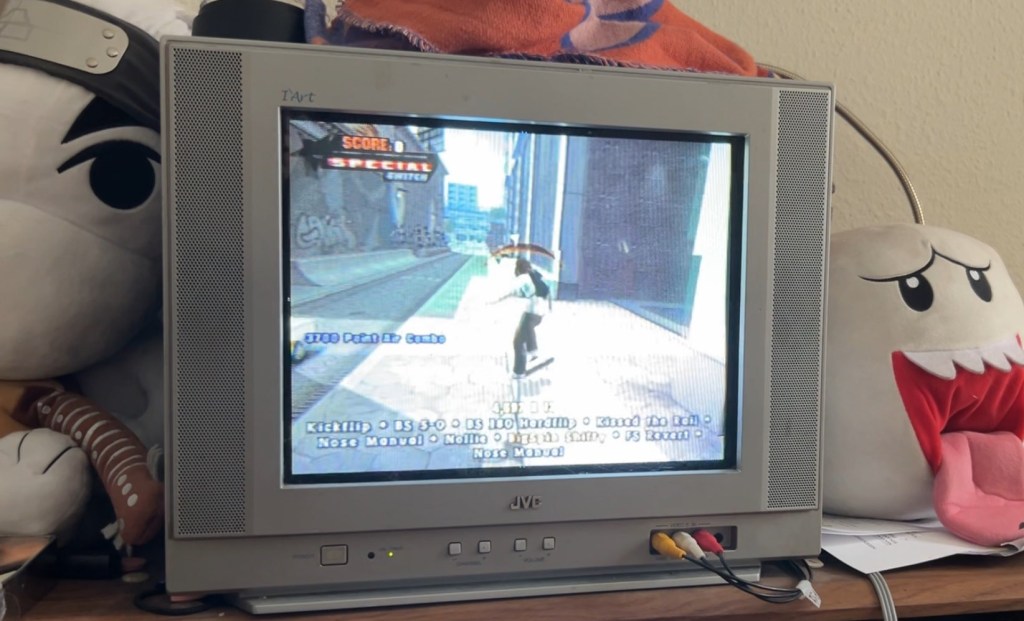

It’s hard to say. I mean, it’s a skateboarding game from a lineage that would fit perfectly into an arcade cabinet. The Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater games typically are score chasers, usually played in two minute challenge runs where you collect SKATE letters and try to get the high score. There are little hints of RPG elements in there, like the distributable stat points you could always invest to get higher ollies, more air time, easier grinds and manuals, and so on, but that’s not really what the games were about. They were about ripping. The absolute absurdity of the lines you can pull off are physically impossible, and it all exists in service to having fun in a silly and arcadey setting. The Underground series though, developed by the now-defunct Neversoft, doubles down on its RPG aspects, and makes this a little more of a difficult question to answer.

Tony Hawk’s Underground is a much more narratively focused game than the earlier Tony Hawk games. Unlike in the Pro Skater games, Underground has you create your own skater, and follows the story of your created character and their rival Eric Sparrow as they travel the world, shoot videos, join competitions, and try to become professionals. It tells the story of you and Eric, beginning as New Jersey locals and becoming global pros, the friendship between the two of you fracturing along the way due to your different goals with skating. Your player character want to be a pro because you love skating, but Eric wants to be a pro because he wants to be rich and famous. Eric’s a sellout, man. He’s not into real soul skating like us. The narrative focus on the game changes the game’s structure completely; where once you were stuck on the board and only able to play two minutes at a time, Underground wants you to step off the board sometimes and really exist as your character in this cartoonishly skateable version of the world Neversoft created. Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4 was the game that began this shift in the series, as that was the game that first got rid of the two minute timer and introduced NPCs into the world that would give you challenges to complete. Underground fully completes this shift by adding real narrative, a greater focus on your player created character, and eventually choices of which actual skate team you want to join (including Girl, Element, Zero, Birdhouse, and a couple more real skate teams). The character creator is weird and fun, and at the time you could even send in a picture of your face to Neversoft so that they could scan it and give you a passcode that you could enter, putting your actual face onto your character in the game. This is a game in part about your character’s individuality, and they wanted you to be able to express your player character both through skating and through its many customization options.

Throughout the story of both Underground games, you travel from city to city completing specific challenges that the people you meet will ask you to do, and doing so gets you closer to progressing the story. Some of the challenges are unique, like the one in the beginning of the game where you have to “take a dog for a walk” (grab hold of the dog’s leash and skitch behind him while he runs down the streets) while others just have you collect a bunch of points and move on. You can do these in almost any order you’d like, ignoring as many of the ones that suck as you want. I like the challenges that ask me to do specific grinds, or tricks I don’t usually do. I hate the challenges where you have to drive a car, so I never do those if I can avoid it, but if you like awkwardly steering around a big stupid box that feels bad and isn’t fun, you can go ahead and find those first too. The player’s choice is important here; the Underground games want you to have your own adventure through this deeply weird, extremely made-in-2003 world. In a way, it’s sort of all about making the game your own experience, with all of this and the trick creators and level editors. They want you to experience your version of Tony Hawk’s Underground and find your story of what it means to skate until you become pro. It really is an incredibly tight and fun skateboarding game. Is it realistic or simulator-like in the way Skate or Session or any of those others are? Definitely not. But building a combo in these games and maintaining it is challenging in the right way, and can almost be meditative in the way I had spoken about skating in the beginning. It is good to be forced to lock in by something you enjoy.

With the interest in narrative comes a stronger focus on the weird RPG elements present in THPS. In the series before Underground, you would be able to increase your stats only by finding stat points hidden in hard to reach places around the world. Here, though, they’ve changed the system completely, and you can now only level up your character by accomplishing certain goals related to each stat. If you want better and faster flip tricks, you have to start doing several flip tricks in one combo to earn it. If you want an easier time balancing on rails, you’re gonna have to first hold a grind for fifteen seconds straight, or do three nose grinds in one combo. If you wanna get better at skating switch, you’re gonna have to do a lot of different tricks and probably start doing the impossible: actually skating switch. All the stat upgrades come like this, meaning the game will reward you for trying to improve your specific skills. If you’re like me and not trying too hard to unlock all the skill points, this also means that your character is naturally going to be better at the style of skating that you as a player gravitate toward the most. I like street skating, and love grinds and slides and manuals and technical flip tricks, so that’s what I ended up with most, but someone more into vert or transition skating might find that their character ends up with more air time or better lip tricks. I didn’t remember this skill system from when I played this game when I was younger, so when I first found out about it, I thought, “oh yeah, it’s almost sort of like Skyrim‘s skill system!” Actually, though, this came about half a decade earlier, so if anything, Skyrim is sort of like Tony Hawk’s Underground (and if we’re being pedantic, we could even say Tony Hawk’s Underground‘s progression is sort of like Final Fantasy II lol).

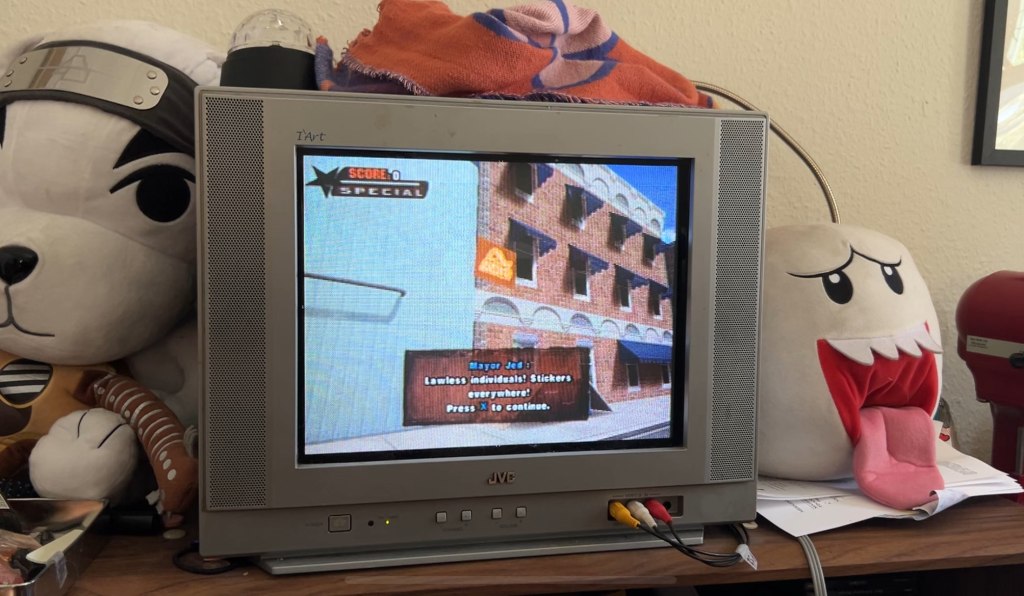

Perplexing all of these weird mechanical things going on with the game is the tone and story itself, especially in Underground 2. This second game as a narrative is more about slapstick comedy than it is about skateboarding. Bam Margera being such a big feature in Underground 2 somehow entirely shifts the already unserious tone to a straight up Jackass movie. There’s already a huge overlap between slapstick stuff and skating in the real world, but this completes the comparison. The game literally opens with you being kidnapped by Bam and threatened with a chainsaw while you and other pros are tied to a chair as a prank. Eric Sparrow pisses and shits himself in the chair. From there it’s all farts, dicks, boobs and bikinis pretty much for the rest of the game, occasionally moving its focus to make fun of the disabled or other marginalized folks. Also reflecting this cultural time period is the soundtrack, which is very of its time; it includes songs like “No W” by Ministry, which opens with a sample from a George W. Bush speech about “fighting a war against evil.” Like I said, it’s extremely 2003, warts, wars and all.

So there’s a character creator, lots of player choice surrounding how you might approach the game and its many obstacles, deep customization options, narrative focus, a hero and a villainous rival, character statistics that reflect who you play and how you play them… but do all of these make it a role playing game? I’ve been doing some digging trying to find the language the developers used during the marketing of these games, and in a 2003 IGN article by Douglass Perry, the company president at the time Joel Pewett says: “It’s an adventure game. It’s different from anything we’ve ever done in the series.” What he actually means by this isn’t completely clear in the article. When I think of adventure games, I think of something like the Monkey Island series, and this is certainly not anything like that. It is an adventure, but is it an adventure game? And if it’s a role playing game, why? What is a role playing game anyway?

Like all genres, this is incredibly tough to define, and as I was starting this blog I actually struggled with this a lot. The question of what a role playing game is, especially in the context of video games, haunted me when I began, and so many people have arrived at so many different answers that it boggles the mind. You could say it’s any game that involves lots of customization and character progression, but then that has to include certain sports games where people might disagree like Tony Hawk’s Underground, or NBA 2k25. You could say it’s any game that involves player choice or other agency over the story, but that would exclude certain games that obviously are role playing games like some entries in Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest. And with some of these definitions, you’d have to include Zelda. I’ve heard it said that role playing video games are games that replicate the systems used in tabletop RPGs, but those systems are so diverse and often not even reflected in many of the role playing video games we have today. What tabletop game plays the way an action RPG like Final Fantasy 7: Rebirth does and don’t say Queen’s Blood? (I’m sure there’s lots, including the TTJRPG Fabula Ultima but you get the idea.) You could even just say, “well, I don’t care, I know a role playing game when I see it,” and like sure, but then how do you talk about the genre if you can’t articulate what it’s made of? It’s really a pretentious and stupid socratic dialogue sort of question. Can you define a chair in a way that includes all things that are chairs and excludes all things that aren’t? “Can you define a role playing game in a way that includes Baldurs Gate, Final Fantasy, and Dark Souls, but doesn’t include Zelda?” Shut up!!!!!!!!!!!

What you can do is identify common themes: they typically (but not always) have stories and setting which make up a large focus of the game, where one or a party of player characters take actions whose effectiveness is determined by statistics, and involve expressive decision making in any one of many different ways. There are sometimes (but not always) dice, NPCs, usually battles, and character progression reflected in the character’s statistics. As much as this is generally (but not always) true, there’s also so many ways where each and every one of these “rules” can be broken as long as it maintains some sort of aesthetic similarity or lineage through inspiration. Sometimes a game might follow none of these rules and still be a role playing game. Maybe you can even follow most of them and still end up somewhere else in genre space. A genre isn’t always a thing you are, it can be a thing you use: I think Tony Hawk’s Underground and Tony Hawk’s Underground 2 are interesting because they are their own unique experiences, dabbling into lots of game genre spaces yet reflecting their own place in the series, in the world culturally, and in gaming. It’s a score chasing arcade cabinet, yes, but it’s also a long adventure-like story where you level up through experience and challenges, and progress by interacting with NPCs. It’s also a game with lots of weird little RPG elements, and it’s a Jackass movie starring Bam, and it’s a park builder game, and it’s a window into the culture of gaming and maybe skating at the time… It’s a lot of things! It’s hard to say that it’s just any one of them. Besides, there are elements of role playing games in seemingly everything now. In Call of Duty‘s multiplayer (or at least the ones I played for a short while on the Xbox 360), leveling up granted you access to more perks, more equipment, more weapons, which in turn changed the way you interfaced with the game. You can get prestige levels, too, which means choosing to reset your level to zero and do the whole thing differently. These are pretty straightforward RPG elements punched right into the game to give a sense of character progression to your multiplayer ranking. Does that make Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 an RPG? Like, no, or I mean, not really, not if you’re being serious. But that doesn’t mean the influence isn’t there; that stuff doesn’t happen without a long history of role playing games and role playing systems being implemented into other work. It’s not just RPG heads that like to see the numbers go up.

I guess my point is that if Tony Hawk’s Underground isn’t an RPG, then there’s a lot of RPGs out there that also aren’t RPGs. But if it is, then everything else kind of is too. And that’s the thing: everything kind of is an RPG, as long as the thing wants it to be. A journal can be an RPG, or a coin flip, or a table full of candles, or a skateboarding video game. Plus, in a world where so many games now have level up systems, and weapons or skill trees that give you silly bonuses like “+2% poison damage on rainy days except when equipped with poison weapons” or whatever, it’s all moot. It’s all role playing man. We’re all just sitting here playing pretend together. So I’m just going to continue my life on the assumption that it’s a role playing game, and therefore it’s fine for me to cover it on my blog. I don’t even have to be right! I can do whatever I want! It’s my website! I own it! Nothing can stop me! I can make the text as

big and red and ugly as I want and nobody can do anything about it.

So that’s where I’ve landed on Tony Hawk’s Underground. The question of what it is doesn’t really matter, I realize. Underground is its own thing, a game that likes skateboards and statistics and points and cars and women in bikinis. Hard to blame them. For the most part, even though I prefer Pro Skater 4, I did enjoy it! So that’s it. Your homework today is to go skate in the real world if possible. Cleanse your palette.