Final Fantasy as a series draws a lot from the theater; its stories always dealing in pathos, and always intending to tug at your heartstrings. Off and on throughout the year, a very good friend and I have both been playing my favorite entry in the series, Final Fantasy IX, and sharing some notes here and there about what’s been working for us. There’s lots of interesting details to mention here that make it my favorite: I really like the self reflective nature of this game, and how that applies to both the characters relationship to themselves (some of whom are going through dark night of the soul stuff) and with the game’s relationship to the franchise (director Hiroyuki Ito says Final Fantasy IX was intended as a retrospective on the series, where they would “return to the roots” of Final Fantasy). It’s self referential, and is constantly revisiting the legacy of the themes, characters, and highly dramatic moments from earlier in the series. A fun example is Beatrix, who feels like taking another shot at Cecil from Final Fantasy IV. This is one of the benefits of a huge body of work like this series: nine entries in, you get to make a game about the memories of your work, and it works like a charm on freaks like me who love a metanarrative.

What continues to come up in my conversations about this game, though, is Final Fantasy IX’s relationship to the stage, the theater, and its countless references to the Bard. The similarities between Final Fantasy and Shakespeare are everywhere – Final Fantasy is, like Shakespeare’s plays, a giant body of work that is heavily invested in themes and narrative techniques like amnesia, mistaken identity, love and revenge, ambition and fate, dramatic irony, insanity, free will… All these tragic and funny and weird human stories and characters lie at the heart of what makes this series work. But Final Fantasy IX is obsessed with the theatrics of it all, too: performances within performances, stage plays and scripts, puppets and audiences. Part of what I love about so many of the melodramas, romances, comedies and tragedies scattered throughout Final Fantasy IX is its continued interest in the theater, and its total, all consuming self awareness about this. So of course, this is the game that opens with a stage performance.

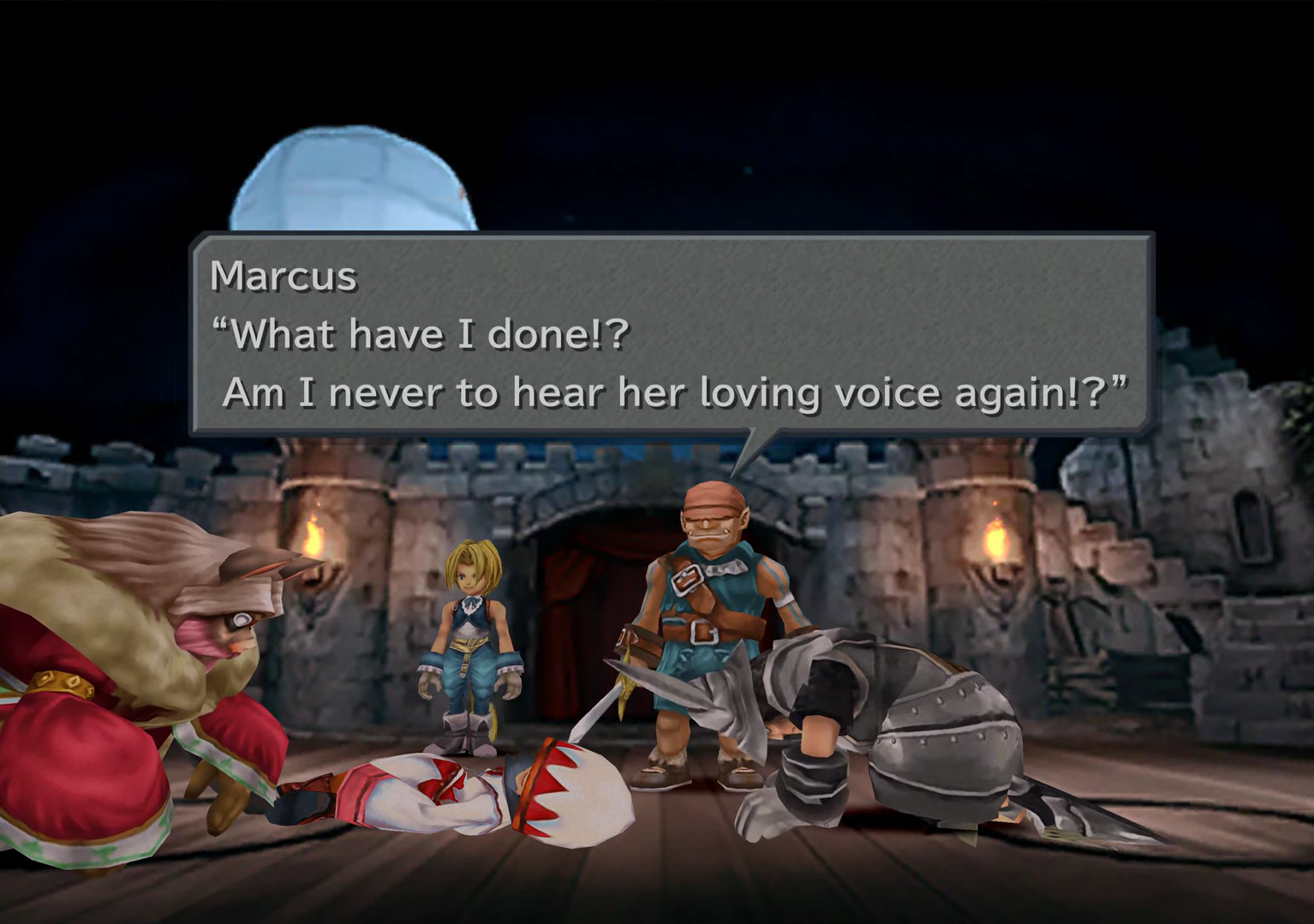

The theater troupe Tantalus is coming to the Kingdom of Alexandria on an airship to give a performance of the play I Want to be Your Canary for all of the nobles, the Queen, and Princess Garnet. I Want to be Your Canary, the fictional stage play, is about a romance between a noble princess and a peasant. In the play, the princess Cornelia and the peasant Marcus find themselves in love, but their love is forbidden by Cornelia’s father, King Leo. At the climax of the play, Marcus draws his blade to cut down the king as revenge for his family and to gain the freedom to marry the princess. Just before he strikes the king down, the princess steps into the blade, saving her father’s life and sacrificing her own at the sword of her lover. Marcus, lamenting that he is cursed to never again feel her soft touch, turns his blade on himself, killing himself on stage and bringing the play to a close. A dramatic climax where the two star crossed lovers, kept apart by the culture of their families, both tragically end their own lives over a misunderstanding between one another? When I tell you we’re doing Shakespeare here, I mean it.

What’s even better is what I’ve failed to mention here: this whole performance is a distraction put on by the thieves in the theater troupe in order to kidnap the real princess in the audience, Princess Garnet. As we follow the plot of this stage play, we also follow this plot to kidnap the princess. The plans of everybody, fictional and even more fictional, fall apart together, and in falling apart the boundaries of each story blend. By the end of this scene, we have all the major characters involved in the kidnapping chasing each other on and off the stage, and in doing so they wander in and out of their part in the performance. Our protagonist Zidane gets on stage first and tells the other actors to improvise, and from that moment forward, once somebody is on the stage, they become players in the performance. When they act, regardless of intention, they are a part of the show. Princess Garnet (who will later rename herself Dagger) is, when she is on this stage, Cornelia, and when Marcus thrusts the sword between her torso and her arm, Cornelia dies. Steiner, the knight who has sworn to protect her outside the fiction of the play, falls to his knees believing Garnet to have been killed. His real grief at what he believes is the genuine loss of her life makes her performance all the more believable for the audience. Final Fantasy IX is about the very blurred line between what is a performance and what is a genuine life, and almost every character throughout the game feels differently about what that means for them. It wants you to be asking: how does one respond to the idea that they may just be a player on the stage?

This is the central conflict behind one of Final Fantasy IX’s most important and thematically central characters: Vivi! Vivi is a black mage, one of many in Final Fantasy. He’s a powerful wizard who controls destructive, elemental magic in the palm of his hands. It just so happens that he’s also the most beautiful little creature in the history of video games. A tiny little wizard who appears to be about nine years old, Vivi’s got a little wizard’s hat that casts a dark shadow over his face such that you can see only his golden-yellow eyes shining through the black. Behind that darkness, though, there is a bright young boy. Vivi has the demeanor of a prey animal. He’s perfect, and I have a rare condition where every time he’s on screen I instantly burst into tears.

It’s revealed in the first act of the game that the black mages in the world of Final Fantasy IX are all mass produced by the Kingdom of Alexandria as weapons of war, and are designed to be mindless and soulless pawns in the kingdom’s army. Vivi being one of these black mages means much of the story throughout the game strongly features Vivi grappling with the question of his autonomy. Is he authentically an individual? Or is he a puppet? Is his fate truly his to decide? Or is he, like many of the other black mages, just playing the role that was created for him, a part of some greater performance that he doesn’t understand? What does it mean for him to be alive as a person now if he was once created to be a weapon of war puppeteered by a corrupted queen? Or worse, a silver haired twink? These are all, generally speaking, important lines of thought for Vivi that become the central questions of his character, and through him, central questions for the game. In what ways does a performance become an authentic self, and in what ways does someone’s authentic self occasionally steer into a performance? Does it even matter if you believe it to be true?

This performance theme is woven throughout the entire game, taken sometimes personally and metaphorically in the case of our black mage, and sometimes literally in the constant references to the stage. Our protagonist Zidane is a thief, but he’s a thief from a theater troupe. In a cave near the deserted village of the summoners, Dagger (formerly Princess Garnet) hides away on a boat, singing to soothe herself. Zidane follows the song and finds her here. She’s moping a little bit. She feels responsible for all the trouble they’ve faced on this journey, feels as though it’s all trouble she’s caused, but Zidane tries to tell her that all of their friends who are here with her are here because this is the path they’ve chosen to be on. Dagger asks why he came with her, and in Zidane’s most relatable moment yet, he immediately begins describing a stage play he’s seen in detail. He says:

“It kind of goes like this… Ipsen and his good friend Colin worked at a tavern in Treno. One day, Ipsen got a letter. The letter was so wet from rain that most of the writing was illegible. The only part he could read said, ‘Come back home’. Nowadays, we have airships and stuff, but back then, it was really hard to travel. He didn’t know why he had to go back, but he got some time off, gathered his things, and set out on his journey home. He walked a thousand leagues through the Mist. Sometimes he was attacked by vicious monsters, but he made it, because his friend Colin was by his side. And then, after much time on the road, he had to ask Colin something: Why did you come with me?”

“And? What was Colin’s answer?”

“Only because I wanted to go with you.”

This is of course the moment that they set sail in their little boat. Now I have to say: this does sound kind of like a shitty play. But I think it’s an excellent little piece of storytelling that beautifully illustrates who Zidane is. Zidane thinks of himself as the Colin in this story, the secondary character who is just here to help his friends. His reason for being here with Dagger is simple: he’s here because he just wants to be here, wants to be with her, and doesn’t need a reason any more complicated than that. It also makes Zidane seem really well read, which makes sense given that he was raised on a theater ship, but is nonetheless some really funny characterization. Important for our purposes here, though, is that it’s incredibly on theme. This is one in a long line of metadramatic moments in this game, just like I Want to be Your Canary, where plays exist within the fiction and are used as plot devices to express something about the characters and the world. This simple narrative maneuver, the creation of so many plays and scripts inside the world of the game, creates such a distinct theatrical culture in this world, and establishes themes that Final Fantasy IX continues to return to until the very end.

My personal favorite of Final Fantasy IX’s allusions to theater comes pretty late in the game, in the form of a prolonged foolproof love letter scheme, which focuses on the hidden and confused identity of a love letter, and the things each character assumes about it. Try to follow along here: Eiko (six year old summoner) employs Doctor Tot (not important) to write a love letter for Zidane. Before Eiko can deliver the letter, she is accidentally shoved off a balcony by Baku (Zidane’s boss/dad) and begins hanging by her shirt from the railing (anime). Baku is tasked to deliver the letter, but gets into an argument with Steiner (loyal knight and giant herb), so he throws the letter on the ground in anger and leaves. Steiner storms off too, and Beatrix (loyal knight and baddie) sees Steiner leaving the letter behind. She picks up the letter to reveal what the good Doctor Tot wrote:

When the night sky wears the moon as its pendant, I shall await you at the dock.

Reading this, Beatrix immediately assumes this is a love letter that Steiner has written to her. Inexplicably, Blank and Marcus (Zidane’s thief friends) catch the letter in the air later and they go to the dock believing that somebody wrote it for Blank. As the night sky wears the moon as its pendant, Eiko, Blank, and Marcus arrive at the dock and become the audience as Steiner discovers the note, reads it, and turns to see Beatrix. This is a really funny series of events to me, and the beginning of a romance which will continue for the remainder of the game. These two characters, originally introduced as competing knights under the same flag, are pulled together by the gravity of dramatic irony. Their love story is based on a series of misunderstandings and changing of hands, but it becomes true despite and because of its falsehood. Once again, Final Fantasy is pretty straightforwardly doing Shakespeare. I’m reminded specifically of Much Ado About Nothing, where the two conflicting characters Benedick and Beatrice (Beatrix!) are each tricked by third parties into believing that the other one is hot for them and, titillated by thought of being subject to the other’s unrequited love, both confess their love to one another. It’s also maybe an allusion to mechanically similar Twelfth Night, where one character forges a love letter in a woman named Olivia’s handwriting, and in doing so tricks a suitor into doing things that actually would make Olivia hate him. There are likely countless other examples in Shakespeare like this one,where two people’s relationship is defined by this dramatic irony. Final Fantasy loves this stuff: these stories about people, their emotions, their relationships to each other and themselves, are the heart of the series and the heart of the theater.

Some other final notes on Shakespeare in Final Fantasy IX: I Want to be Your Canary, the previously mentioned fictional play, literally is about a character named King Leo. Marcus, Cinna, and Puck, all minor characters here, are each names that appear in Shakespeare’s work. Lord Avon, the fictional writer of I Want to be Your Canary, alludes to Shakespeare’s hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. All neat little references that tip the game’s hand toward what it’s really interested in. Eiko’s letter, though, was a moment for me where my read on this game being about theatrics, performance, and what it means to be real or fraudulent really came to the forefront of my mind. Re-examining the game, you begin to see it everywhere.

It also features the primary tension behind Final Fantasy and other role playing games like this, where it has to be about all of this and about actual time battles with big monsters and evil villains. I’m enjoying my replay this time around, and more than anything really enjoying the way it manages to take itself and its emotional content seriously while maintaining this playful tone it always carries. I’ll leave you with my favorite lines from Lord Avon’s famous I Want to be Your Canary.

“Marcus, wilt thou truly cherish me, the king’s only daughter? Or is such a desire too dear to wish for? After our nuptials, shall I become no more than a puppet? A mindless puppet, never to laugh, never to cry? I wish to live my life under the sky. At times I shall laugh, at other times cry. For no life is more insincere than that lived as a masquerade.”

Questions? Comments? Thoughts? Impulses equal parts melodramatic and metadramatic? Email me, if you’re the type of person that likes to send emails: leavingthepartypod@gmail.com

Leave a reply to Ƨky Petey Cancel reply